Passover is performance art of the ancestral kind. A start to finish journey, an Exodus if you will, one everyone is invited to participate in. Even me!

My family wasn’t religious, but a sucker for a good story. Year after year, I waited to hear about the Jews epic journey start to finish. Year after year, I only got the beginning — we were stuck in slavery. And the end — forty years in the dessert. The grand finale being crappy tinned macaroons and flourless chocolate cake.

I helped my mother set the table when she hosted. In her anxiety-driven strive for perfection, she pummeled us with orders and lists, barking instructions on how to assemble our universal props. My sister and I placed them onto a circular plate with symbols of the saga in miniature saucers— horseradish, a shank bone, a boiled egg, and a bowl of salted water that was supposed to simulate tears, but wound up being the only thing that helped you choke it all down between the four prescribed glasses of wine.

As we waited for guests, my mother finished the table with a glass of wine for Elijah the prophet. He was smart enough to sucker the whole of Jewry into getting him drunk once a year, but couldn’t figure out how to get through walls, so someone would have to get up and open the door in a grand production.

The book of instructions, called a Haggadah was at everyone’s setting. Some copies were wine stained, many were torn, and none were uniform, because even after 5,000 plus years we don’t all agree on one script. Nor should we. After the requisite complaining about the traffic they suffered to get there, we were ready to begin.

Someone took a piece of cloth covered matzah, broke it in half, put one side on the seder plate, while the adults tried to distract the kids long enough to hide the other. In theory, the hidden half was supposed to be dessert. We took that as a sign of great suffering and were grateful our parents handed us money for it and served little jelly candy instead.

A highlight in most seders features the ubiquitous ear worm of a song named, Dayeinu. The Hebrew lyrics are about if God had only let us out of Egypt, it would have been enough. If only he’d swallowed up Pharoah and not the Egyptian army, that would have been enough. If only I would end the explanation here, and not go on, that would have be enough, too— you get my point.

It crescendos, growing louder. Fellow rescued wanderers wake up from their long winded journey and 20 minute starvation to bang tables until the silverware jumps. A good Dayeinu was always enough.

I wanted more of a coherent thread though. Stop throwing matzah at me! Tell me what happened.

At Aunt Augusta’s seder in her tiny apartment on the lower east side, we’d start out well, maybe talk about the cow disease and the slaying of first born for five minutes. But once we ate those icons, she dropped ground fish onto our plates and lectured us about how humans learned nothing from all these years of oppression, that given the opportunity, those in charge would step on the worker’s back to get ahead. Every time.

A perpetual cigarette dangled from the corner of her mouth. She was never near an ashtray, always soapboxing through eyes squinted against the smoke. I was convinced I could taste it in the food. I adored her so much, I named my son after her.

Aunt Augusta droned on way beyond the fruit jello salad, matzah and stewed prunes until, slippers shuffling against cracked kitchen linoleum, she reacquainted us with her carton of carbon copied letters she’d shot off like shrapnel to various local officials.

That show devolved into a lazy suzan of excuses to be angry at management, while my father — management — rolled his eyes and checked out of dinner without ever leaving the table.

Our Dayeinu was raucous though. My mother nudged me to pretend to give up finding the broken piece of matzah, knowing the quarter reward wasn’t worth the search.

My father befriended a Yeminite Israeli family to celebrate with. There were nearly forty human beings in a two bedroom house somewhere in Queens. This was more dinner theater than drama, which gave me hope of understanding a plot, only it wasn’t in English.

I got to carry fragrant, delicious, leaven free foods as they piled up on the plastic kitchen tablecloth. The indulgent feast was cooked by a small, hunched woman with rotting teeth, whom I knew for ten years and never once saw outside her kitchen or without a smile.

I was pretty sure the stories they were telling had nothing to do with God, but their joy came through loud and clear.

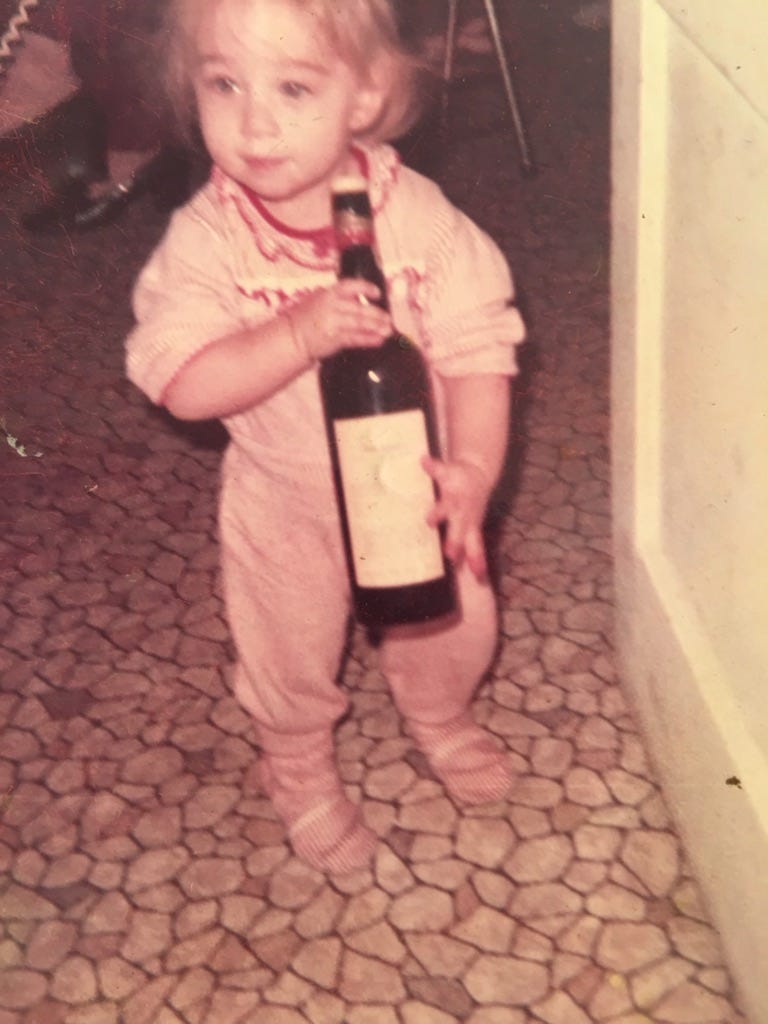

By the time they got through the first few glasses of wine, they broke into smaller tables to play high stakes backgammon, sipping Turkish coffee through sugar cubes in their teeth, while I stole the half empty bottles of the sickeningly sweet Manischewitz Grape Extra Heavy Malaga and made out with a child of Abraham on a moldy mattress in a half finished basement, the story lost to me yet again.

Their Dayeinu sounded more like Ninety-Nine Bottles of Beer on the Wall and I loved every ground shaking minute. I wanted to find the matzah in that house where the competition was fierce and they offered $150, 1980 something dollars!

While opening night was a romp, second night we went to the intellectual branch of the family. Aunt Nancy’s was erudite and included some Yiddish along with several references to the New York Times and NPR. For 10 minutes they spoke eloquently about the struggles of the immigrants who came before the war, and those that died. They sang songs to those who came after, and the refugees still coming, and the women who always wind up carrying most of the heavy load.

Their Haggadah was a forerunner in the pronoun game though the forefathers/foremothers elongated the seder to 12 minutes which threw my father into an obviously contained rage. Still, my mother felt comfortable at her brother’s house, where she spoke the language and his wife was among her closest friends.

In my teens, I passed out in their spare bedroom in the Bronx by the second glass before anyone found the matzah, though I heard the Dayeinu through my drunken sleep. I didn’t feel too bad. The communists they were would have made me share my matzah finding haul with my sister, anyway.

Still, there were big pieces of the story missing. What was it? Where was the production worthy of 5,000 years of rehearsals? It remained a mystery until well into my college years when someone suggested I read it straight from its Biblical source material. Which I did. But found it lacking in subtlety.

There have been many productions since. There was one I began in Los Angeles, haltingly, and definitely not by the book despite my best intentions. My friend and her father came, bringing macaroons that were on an entirely new level, one I aspire to, but have yet to attain. I make them every year now and think about him, a spectacular human being.

At one, I was joyously pummeled with tiny plastic figurines of plagues, which I found oddly effective. At others I have been bored to tears. I have traveled to stranger’s tables, to communal halls, to banquet rooms, and had low key ones with just my husband and my children, where I got through the ritual without being heckled. To my face, anyway.

I have to come to realize, that like with a funeral, it’s better to be an audience member than the star.

The best ones have killer soundtracks. Dayeinu would have been enough, but the music ranges from sweet Yiddish lullabies about apples and honey, to stacking songs about selling livestock for ancient currencies called, Zuzim!

One of my favorite’s was my friend’s mother. Some people perform Passover, others embody it. She sang with enough joy to lift the entire table, even if she was a taskmaster. Her melodies were my inspiration the moment I met them.

Tonight’s seder will be music with warm friends, family, delicious food, and tipsy teasing. Everything that’s important to me. Because after all this time, I’ve learned, my Passover story is only a tiny grain of sand on a beach nearly 6,000 years long.

I’ve stopped looking for someone to present me with a narrative that is ultimately disappointing. The beginning of the story is always birth, while death is its foregone conclusion. The rest is what gets fudged, failed, celebrated and shared. Not everyone will get my meaning, not many pick up my inflection, but as long as I weather the bitterness, eat some dry chicken and sweet carrots, let a stranger share my table, I get to rejoice in my very own Dayeinu. For me, that is more than enough.

**This story was originally posted on Medium during passover 2022, and since I’ll be traveling for the festivities, I’m playing this rerun early.

Whatever you’re celebrating, I hope it is full of love and family, friends and the posse you don’t get to see too often.

In Hebrew we say, Pesach Sameach — a happy Passover.

In Yiddish we offer, Assizin Pesach — a sweet Passover.

In Ladino, it’s Pesack Alegre — a cheerful Passover.

And of course, Happy Easter to the many I love who celebrate. That last supper, while they were all gathered around the table, despite everything going on behind the scenes, they began telling each other the story of Passover. I bet they didn’t make it to the end either. And it was, Dayeinu.

This still warms my heart after a year. I miss you at my Seders. ☹️ Peasach Alegre, mi amiga lindah!

Katie, I remember a seder at Phil and Nancy's, featuring my beloved Haggadah from the feminist group I used to celebrate with in Vancouver, at which you declared the text "not traditional" enough for your taste. I presume your tastes have changed since then--and I spared you my rather academic views on the invention of tradition. But I do miss family at such times...Love,

Carla